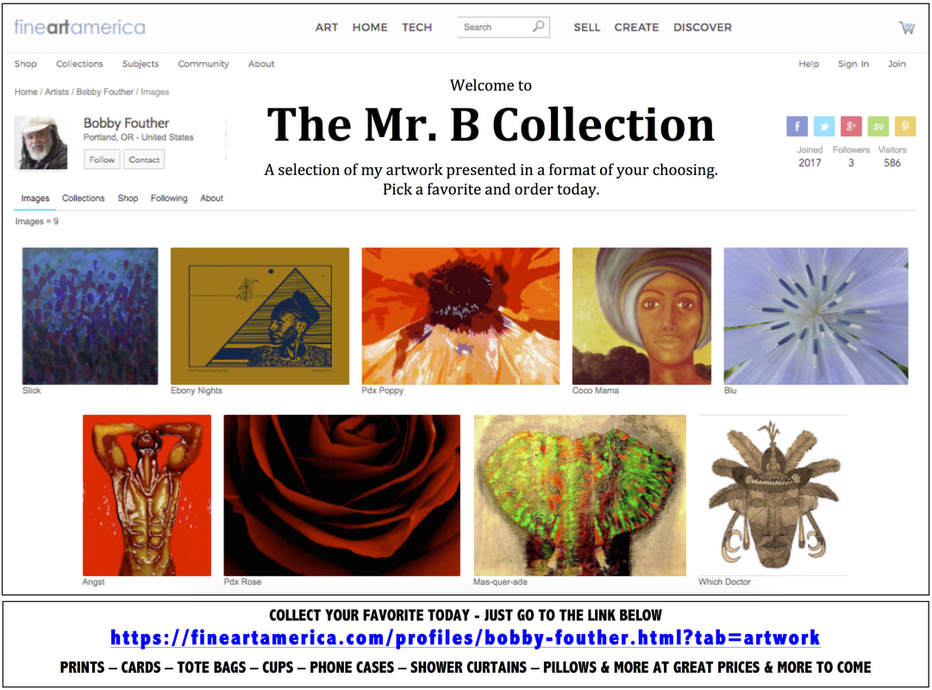

MY ART STUDIO ONLINE

ORDER YOUR FAVORITE.......MR.B

https://fineartamerica.com/profiles/bobby-fouther.html

ORDER YOUR FAVORITE.......MR.B

https://fineartamerica.com/profiles/bobby-fouther.html

EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] TELEPHONE NUMBER 503-422-3076

Home / Artslandia Features / June-July 2017

Mr. Bobby: Dance Hub

BY JAMUNA CHIARINI & OLUYINKA AKINJIOLA

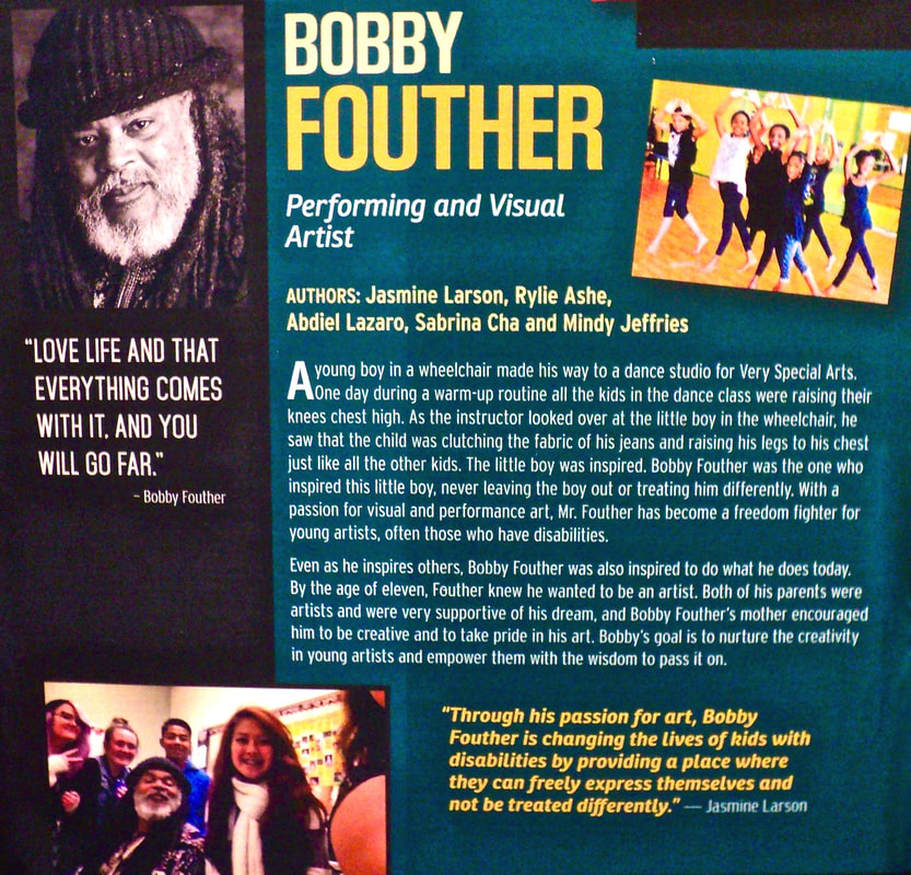

When the History of the performing arts in Portland is written, the chapters for the years from 1980 to the present will include a host of references to Bobby Fouther. His career has touched many of the mainstream arts organizations in the city, including Oregon Ballet Theatre, BodyVox Dance Center, and White Bird dance, and has tracked many of the most important African American arts groups from that time: His own Herero Dancers, Bruce Smith’s Northwest Afrikan American Ballet, and such theater companies as Portland Black Repertory Theater, Sojourner Truth Theater, and PassinArt: A Theatre Company.

These have been short-lived, except for PassinArt that was founded in 1982, more an indication of mostly white Portland’s funding patterns than the artistic levels they reached. Born on Labor Day in 1950, Fouther grew up in a Portland Black community that crumbled as he grew older, neighborhoods decimated by the building of Interstate 5, Emanuel Hospital, Memorial Coliseum, and decades of redlining by the city’s banks and neglect, if not outright hostility, by city government. It’s a testament to Fouther’s talent and persistence that he’s engaged so many audiences, including so many children, with his art, dance, theater, visual arts, and costume design, primarily.

“Mister Bobby was and is not only a dancer but a total artist,” says fellow choreographer Ruby Burns. “He is able to conceive and create from costumes, choreography, music, and most importantly, [he is able to] develop dancers.” And choreographer Josie Moseley describes one of his primary attributes: “He had a welcoming way, a disarming radar that pulled people into his concentric circle. It was really wonderful to see a MAN like that.”

Fouther has taught at Portland State University, served on the curriculum development committees for the Children’s Museum, The World Affairs Council of Oregon, and Portland Public Schools, and served as artist-in-residence in programs sponsored by the Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Arts Commissions and the National Endowment for the Arts, among many other credits.

Where did that talent and persistence come from? As with many artists, for Fouther it started at home.

Fouther’s Mother, Ellen Wood, was born in 1927 and was a dancer. She studied ballet at the Marcelle Renoux’s Renoux Dance Studio, which Fouther thinks was probably the first studio to take a black student in Portland. In the late 1940s, Wood danced with the Don Strong dance company until Strong left town and the group disbanded.

Ellen from Portland married Robert Lee Fouther, Sr. from Birmingham, Alabama, and soon had two children, first Bobby, born in 1950, and then Liz Fouther-Branch two years later. After Bobby and his sister were born, Ellen went to work. But she continued to do art in her home, and she encouraged her kids to do the same.

“We had dragons on the wall, a rice paddy with Asian people on the wall,” Fouther remembers. “And a drawer with stuff for us to do. Because we didn’t have any money, we had to make gifts for Christmas, birthdays, whatever. She would say go to the drawer, and it would be full of stuff. And we always had that to do.”

After a basement mishap with a chemistry set, Fouther remembers receiving an art case with paints, “so any experimenting I was going to do was going to be mixing that, so here I am today,” he says, laughing.

“I was inquisitive. I really was. I’m sure I was a real challenge for her all the time, but she answered all my questions.” And when he turned 14, he got a chance to exercise his creativity in a new way: “At 14 she said, ‘I’m not buying anymore clothes for you. I’ll buy you shoes.’ I figured out how to use the sewing machine,” Fouther says. “I looked really crazy and goofy for multiple years, but I didn’t care; it was my stuff.” What did he learn from that experience? “The fearlessness to be creative and accept what goes with that.”

Fouther’s mother wasn’t the only creative force in his life. When Fouther was six or seven, his mother married his stepfather, James Benton (Sweet Baby James Benton), a blues singer, and Benton was famous in Albina for “The Backyard,” a converted garage that served as a club—with a barbecue pit, theater seats, and even putt-putt golf holes. “All the artists came to our house 24/7,” Fouther recalls. “During the day, my sister and I were dancing in our socks in the kitchen to Diana Ross and The Supremes, the Four Tops, and The Temptations, and at night I was listening to Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and all of that kind of music out of my bedroom window.”

Fouther was 11 years old when his mother told him he that he could do whatever he wanted to do and go wherever he wanted to go, just as long as he got himself there on his own. “She never stopped me,” he said, “She never said no. It allowed me to fully develop my creativity really early on.” It was also around this time that he encountered racism for the first time in the larger Portland community and realized that not everyone lived like he did at home.

Fouther remembers a trip to a restaurant with some other kids to buy some ice cream they’d seen advertised in the window. “We went in there and my friends froze, and one of my friends said, ‘Do you see that?’ And there was a ‘We do not serve Negroes’ sign up on top of the freezer. And I didn’t know what a Negro was, so I’m like, ‘What? What?’ (laughing), ‘cause I want ice cream. So we never got it from there.”

“It’s been interesting living here,” Fouther reflects. “I’ve had a shotgun held on me. I’ve had the police try to pick me up. I’ve had the police take me home for riding my bicycle.”

Fouther Attended Jefferson High School, which at that time had very little in the way of an arts program. He would get some roles in theater department productions but found himself in the costume shop more often, and when he went to Portland Parks & Recreations programs, he was one of the “only ink dots in a sea of white people.”

He had similar problems at Lane Community College and the University of Oregon, where he also got some roles in theater department productions, but again found himself more often in the costume shop. “I just roll with the punches, so that’s why I sew,” Fouther says. “I make costumes. I do sets. I just stayed there and did all the jobs. And it was interesting.”

During the ‘70s, Fouther’s creative outlet was fashion. “I was making clothes. I was making fashion, doing fashion shows, and stuff like that. At this point in time, I got really frustrated with the cultural situation here, and so I was trying to figure out what can I do, where I can just visit schools and do something cultural?” So Fouther recruited some of the models from his fashion work and some local dancers and started a dance company, Herero Dancers [named after the Namibian tribe that was massacred by the Germans in a land grab in 1904], “to do the cultural stuff I thought should be here. And then we were getting these school gigs. We got put on Young Audiences. We were doing everything. That ended up being the professional piece of me, doing dance. It was really satisfying, going to schools and showing a different way of being to kids other than the stereotypical thing.”

A gifted group of African-American dancers organized around Fouther, Ruby Burns, and Bruce Smith, performing in Fouther’s Herero Dancers and Northwest Afrikan American Ballet directed by Smith. Instruction in various African dance forms was part of the program and so was the wide-ranging dance experience that Burns had before she came to Portland. Burns’ goal was to make African dance central to the story and lay everything else on top of that.

Fouther also drew experience from his work with different dance artists that came through Portland to teach at Jefferson High School and through his regular attendance at the International Conference of Blacks in Dance. “I have always been the mountain comes to Mohammed type of person,” he said and recounted meeting Katherine Dunham, Talley Beatty, and Alvin Ailey, among others.

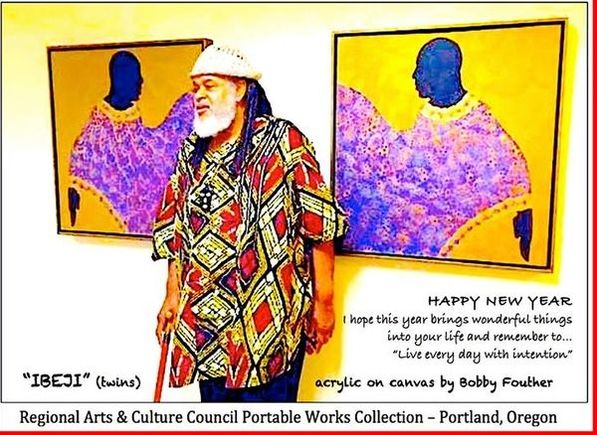

Today Mr. Bobby is busy painting and making art of all kinds, teaching AFRO/KIDWORKS Dance for Every Child, and piecing together his family’s history from a suitcase of old photos recently given to him by his cousin Arvoll Rae, passed down to them from their Great Aunt Della. These photos are a missing piece in understanding the breadth of his family’s history that began in the South, moved north with The Great Migration, and then farther north into Canada due to the Jim Crow laws in Tulsa, Oklahoma (Black Wall Street), ultimately separating him from his larger extended family. The genealogical work will culminate in a dance theatre work and gallery showing.

When the History of the performing arts in Portland is written, the chapters for the years from 1980 to the present will include a host of references to Bobby Fouther. His career has touched many of the mainstream arts organizations in the city, including Oregon Ballet Theatre, BodyVox Dance Center, and White Bird dance, and has tracked many of the most important African American arts groups from that time: His own Herero Dancers, Bruce Smith’s Northwest Afrikan American Ballet, and such theater companies as Portland Black Repertory Theater, Sojourner Truth Theater, and PassinArt: A Theatre Company.

These have been short-lived, except for PassinArt that was founded in 1982, more an indication of mostly white Portland’s funding patterns than the artistic levels they reached. Born on Labor Day in 1950, Fouther grew up in a Portland Black community that crumbled as he grew older, neighborhoods decimated by the building of Interstate 5, Emanuel Hospital, Memorial Coliseum, and decades of redlining by the city’s banks and neglect, if not outright hostility, by city government. It’s a testament to Fouther’s talent and persistence that he’s engaged so many audiences, including so many children, with his art, dance, theater, visual arts, and costume design, primarily.

“Mister Bobby was and is not only a dancer but a total artist,” says fellow choreographer Ruby Burns. “He is able to conceive and create from costumes, choreography, music, and most importantly, [he is able to] develop dancers.” And choreographer Josie Moseley describes one of his primary attributes: “He had a welcoming way, a disarming radar that pulled people into his concentric circle. It was really wonderful to see a MAN like that.”

Fouther has taught at Portland State University, served on the curriculum development committees for the Children’s Museum, The World Affairs Council of Oregon, and Portland Public Schools, and served as artist-in-residence in programs sponsored by the Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Arts Commissions and the National Endowment for the Arts, among many other credits.

Where did that talent and persistence come from? As with many artists, for Fouther it started at home.

Fouther’s Mother, Ellen Wood, was born in 1927 and was a dancer. She studied ballet at the Marcelle Renoux’s Renoux Dance Studio, which Fouther thinks was probably the first studio to take a black student in Portland. In the late 1940s, Wood danced with the Don Strong dance company until Strong left town and the group disbanded.

Ellen from Portland married Robert Lee Fouther, Sr. from Birmingham, Alabama, and soon had two children, first Bobby, born in 1950, and then Liz Fouther-Branch two years later. After Bobby and his sister were born, Ellen went to work. But she continued to do art in her home, and she encouraged her kids to do the same.

“We had dragons on the wall, a rice paddy with Asian people on the wall,” Fouther remembers. “And a drawer with stuff for us to do. Because we didn’t have any money, we had to make gifts for Christmas, birthdays, whatever. She would say go to the drawer, and it would be full of stuff. And we always had that to do.”

After a basement mishap with a chemistry set, Fouther remembers receiving an art case with paints, “so any experimenting I was going to do was going to be mixing that, so here I am today,” he says, laughing.

“I was inquisitive. I really was. I’m sure I was a real challenge for her all the time, but she answered all my questions.” And when he turned 14, he got a chance to exercise his creativity in a new way: “At 14 she said, ‘I’m not buying anymore clothes for you. I’ll buy you shoes.’ I figured out how to use the sewing machine,” Fouther says. “I looked really crazy and goofy for multiple years, but I didn’t care; it was my stuff.” What did he learn from that experience? “The fearlessness to be creative and accept what goes with that.”

Fouther’s mother wasn’t the only creative force in his life. When Fouther was six or seven, his mother married his stepfather, James Benton (Sweet Baby James Benton), a blues singer, and Benton was famous in Albina for “The Backyard,” a converted garage that served as a club—with a barbecue pit, theater seats, and even putt-putt golf holes. “All the artists came to our house 24/7,” Fouther recalls. “During the day, my sister and I were dancing in our socks in the kitchen to Diana Ross and The Supremes, the Four Tops, and The Temptations, and at night I was listening to Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and all of that kind of music out of my bedroom window.”

Fouther was 11 years old when his mother told him he that he could do whatever he wanted to do and go wherever he wanted to go, just as long as he got himself there on his own. “She never stopped me,” he said, “She never said no. It allowed me to fully develop my creativity really early on.” It was also around this time that he encountered racism for the first time in the larger Portland community and realized that not everyone lived like he did at home.

Fouther remembers a trip to a restaurant with some other kids to buy some ice cream they’d seen advertised in the window. “We went in there and my friends froze, and one of my friends said, ‘Do you see that?’ And there was a ‘We do not serve Negroes’ sign up on top of the freezer. And I didn’t know what a Negro was, so I’m like, ‘What? What?’ (laughing), ‘cause I want ice cream. So we never got it from there.”

“It’s been interesting living here,” Fouther reflects. “I’ve had a shotgun held on me. I’ve had the police try to pick me up. I’ve had the police take me home for riding my bicycle.”

Fouther Attended Jefferson High School, which at that time had very little in the way of an arts program. He would get some roles in theater department productions but found himself in the costume shop more often, and when he went to Portland Parks & Recreations programs, he was one of the “only ink dots in a sea of white people.”

He had similar problems at Lane Community College and the University of Oregon, where he also got some roles in theater department productions, but again found himself more often in the costume shop. “I just roll with the punches, so that’s why I sew,” Fouther says. “I make costumes. I do sets. I just stayed there and did all the jobs. And it was interesting.”

During the ‘70s, Fouther’s creative outlet was fashion. “I was making clothes. I was making fashion, doing fashion shows, and stuff like that. At this point in time, I got really frustrated with the cultural situation here, and so I was trying to figure out what can I do, where I can just visit schools and do something cultural?” So Fouther recruited some of the models from his fashion work and some local dancers and started a dance company, Herero Dancers [named after the Namibian tribe that was massacred by the Germans in a land grab in 1904], “to do the cultural stuff I thought should be here. And then we were getting these school gigs. We got put on Young Audiences. We were doing everything. That ended up being the professional piece of me, doing dance. It was really satisfying, going to schools and showing a different way of being to kids other than the stereotypical thing.”

A gifted group of African-American dancers organized around Fouther, Ruby Burns, and Bruce Smith, performing in Fouther’s Herero Dancers and Northwest Afrikan American Ballet directed by Smith. Instruction in various African dance forms was part of the program and so was the wide-ranging dance experience that Burns had before she came to Portland. Burns’ goal was to make African dance central to the story and lay everything else on top of that.

Fouther also drew experience from his work with different dance artists that came through Portland to teach at Jefferson High School and through his regular attendance at the International Conference of Blacks in Dance. “I have always been the mountain comes to Mohammed type of person,” he said and recounted meeting Katherine Dunham, Talley Beatty, and Alvin Ailey, among others.

Today Mr. Bobby is busy painting and making art of all kinds, teaching AFRO/KIDWORKS Dance for Every Child, and piecing together his family’s history from a suitcase of old photos recently given to him by his cousin Arvoll Rae, passed down to them from their Great Aunt Della. These photos are a missing piece in understanding the breadth of his family’s history that began in the South, moved north with The Great Migration, and then farther north into Canada due to the Jim Crow laws in Tulsa, Oklahoma (Black Wall Street), ultimately separating him from his larger extended family. The genealogical work will culminate in a dance theatre work and gallery showing.

EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] TELEPHONE NUMBER 503-422-3076